A review of Randall Watson’s No Evil is Wide written by Cliff Hudder

Discounting Sophocles—whose Oedipus presented a character both sleuth and culprit way back circa 450 BCE—it’s worth recalling that what we think of as “the detective story” is the invention of a poet. Edgar Allan Poe, American versifier, adding to his innovations in horror and science fiction, first introduced mid-nineteenth century readers to tales of crime and investigation in works like “The Purloined Letter” and “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” delivering up a genre equipped from its genesis with many of the ingredients common today: locked rooms, sidekicks, even the amateur nature of the wily crime solver. Poets since have been regularly drawn to the form, as witness Cecil Day-Lewis’s Nicholas Blake novels that made him, in addition to his Laureate status, one of England’s most popular detective writers, and—a personal favorite—Delacorta, pen name of French poet, Daniel Odier, who found commercial success with the Diva series, books that eschew the joys of multi-layered poetic imagery for spare, quick-paced, stripped-down prose that reads like a marriage between a screenplay and a text message. In Randall Watson we find the latest to join the ranks of poet-turned-detective-author in his novella, No Evil is Wide (Madville 2018), a surprising and satisfying new turn on Poe’s invention that, to say the least, does not go the eschewing-joys-of-multi-layered-poetic-imagery route.

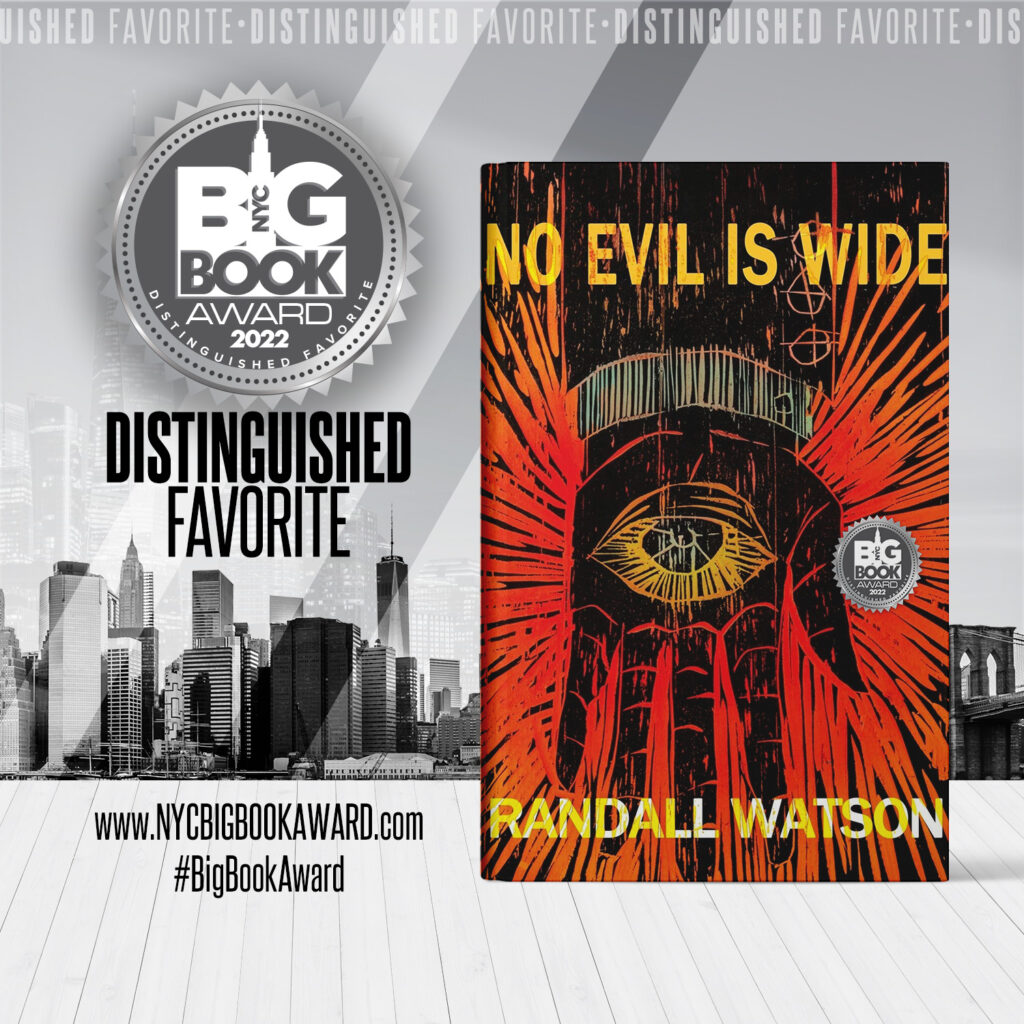

Watson is the author of two books of poetry, including The Sleep Accusations (Eastern Washington University), a recipient of the Blue Lynx Poetry Award in 2004. No Evil is Wide is a revised version of a work first published as Petals in the pages of Quarterly West, a winner of that journal’s prize in the novella category, judged by Brett Lott in 2007, and available until now only in the pages of that publication. Hopefully this stand-alone edition will broaden its audience. The bookis innovative enough that to even call it a “detective story” risks much. It’s something like applying the label to Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo—accurate but insufficient. Yet I’ll traipse out on that limb, for, though the un-named, first-person narrator never identifies himself as such, I can’t help but think of him as “The Detective.” A key reason is the book’s voice: a channeling of classic noir loners like Sam Spade and Philip Marlow, filtered here through the dark urban vision of Baudelaire. Or is it a sharp eyed Chekhovian gift for detail? No longer the bright glint on a shard of glass, the imagery in the novella has been updated, honed. We stumble over “rusted sheetrock screws on the oil darkened ground like the shells of dead insects.” In a description that seems lifted from a late-night movie voiceover, we learn that the light above an alley door is “wavering like a sixth martini.” The narrative voice is as learned as it is hard-boiled, weaving allusions from all rungs of high, low and pop culture—William Carlos Williams, Elton John, Wallace Stevens, Elvis Costello—delivering all with distinct and memorable twenty-first century twists. Instead of Eliot’s “patient etherized upon a table,” the evenings in No Evil Is Wide emit “a soft glow the color of a tanning bed that has somehow made its way into the air.” Watson has a gift for taking his imagery one step further than expected, yet landing on something wholly familiar nonetheless, as anyone who’s ever looked into “the glazed eyes of a woman who has decided to leave you without sharing a word about it” can attest.

This, the sureness of language and imagery, displays the Randall Watson who is by training and temperament not a fiction writer but a poet, and an interesting one—an artist I’ve always roughly categorized alongside Stevens for his work’s variety, surprising visual quality and, well… difficulty. In Watson’s best poems readers encounter both challenging, take-no-prisoner linguistic pyrotechnics, and an exhilarating, building tension. All well and good for award-winning poetic volumes and coffee shop thrills, but can it be extended over 135 pages of prose? Adventurous readers, I predict, will answer yes. Just as an innovative jazz piece like Chic Correa’s “Mosaic” is recognizably grounded in straight ahead, twelve bar blues, here Watson’s mosaic is draped snugly around the genre he’s chosen for riffing: the evocative personality of the solitary seeker of truth, linked with the “what-happens-next?” pulse of his ongoing “case.”

Not a crime-solver, per se, The Detective’s task in No Evil is Wide is to find “the missing,” here a young woman (also un-named) who has fallen into a life of drugs and prostitution, and who ends up casting a powerful spell over him. We come to understand that she is “missing” in a sense more profound than the mere fact that her parents can’t locate her. Indeed, all of the gumshoe touchstones that bring coherence to the narrative come equipped with additional, metaphysical baggage: the girl understands she isn’t selling anything so mundane as sex, for example, but “the chance to believe in something … it is this kind of happiness that people will pay twice for.” The narrator realizes that he wouldn’t even bother to take up this search in the first place if the stakes weren’t higher than those usually encountered by a private eye. “I know how one emptiness can seek another,” he admits. Other classic ingredients underpin the weave of language. The novella comes complete with a dark, inexorable nemesis, Carpenter Wells, one of the only named characters, and a figure just as well-heeled as the narrator. (Through character-building flashbacks, we learn that The Detective has, by chance, been struck financially independent. He’s even more “not in it for the bucks” than iconic characters like Jake Gittes.) Wells has “the money to turn his anger into a question, where my blood is its answer,” and this threat looms over the pages at every turn.

The story unfolds in a manner as playful as it is dark, occasionally sliding into list-like evocations that bring to mind those juxtapositions it used to be popular to use for tagging postmodern novelists as postmodern novelists. Watson lives in Houston, Texas, and although it’s impossible to call that the setting of the novella, it’s intriguing to wonder if the crowded, uncategorized commercialism of feeder roads and un-zoned properties of that sunbelt city have seeped into the narrative. No matter the exact urban setting, in another Oedipal echo—wherein the plague of society owes its infection to the dark interiors of the guilty parties—what’s obvious is that the center in this place is not holding. It is, in fact, not holding AF. “[T]hat was the year that people came to believe the world was changed,” the narrator notes. “No one knew how or why, but it was a feeling that spread from one person to the next.” A particularly unnerving apocalypse goes on around our hero as he continues his search, its details described in frenetic, escalating fashion. “There were explosions. Buildings trembled. A woman cleaning her car at a gas station was shot in the back of the head by the son of a neighbor who kept his gun hidden in a box of Lucky charms.” Happily, the bombs are so random that they occasionally destroy things that need to be destroyed. Less happy: short scenes deliver up images like the particularly nasty bodyguard who, for fun, slips alligator eggs into the nest of a swan.

Good times.

To read the book, as I confess did, during a week that featured continent-wide bomb threats, a grocery store hate crime, and the gunning down of eleven worshipers in a Pittsburg synagogue, only serves to underscore No Evil is Wide’s unnervingly accurate sensitivity to society’s present day, threaded pulse. Not to spoil an effect which should come as no surprise, unlike Oedipus, No Evil makes no guarantee that solving the “mystery” solves the plague. What the novella does deliver is a developing character who grows both increasingly world-weary, yet increasingly intent on getting his story across. “Do you understand?” he asks in a direct address through the fourth wall. “Can you hear me?” This is in addition to a culminating scene of such satisfying mythological resonance, violence and retribution that one can nearly hear the author of “Masque of the Red Death” applauding with appreciation in the background. Simply put, No Evil Is Wide is a terrific example of how the elements of formula can be shaped to more than formulaic ends. The late Swedish novelist Henning Mankell, creator of Wallander, put it well: “the mirror of crime is an efficient way to talk about contradictions in society, between men and women, dreams and reality, rich and poor.” The poetic impulse is, perhaps, not quite so interested in efficiency, but Randall Watson’s novella serves as an evocative moral mirror nonetheless. Look into this compact but densely crafted volume for an experience of those baseline foundational aspects of human life and human value that have attracted all writers for centuries, delivered in a manner as complex as “The Idea of Order at Key West,” as urgent as the headlines on your iPhone’s feed.